Killer Whales

Introduction

Spyhopping Killer Whale (left) and Pod of Killer Whales (right). (GA images) |

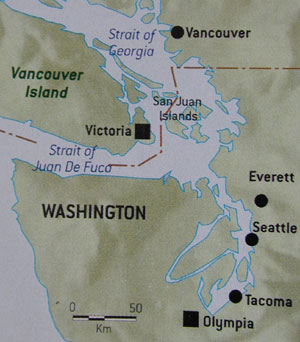

| Found in all oceans of the world, the killer whale is considered to be the same species everywhere. Since killer whales spend about 95 percent of their time underwater (as do most of the cetaceans) it has been difficult to learn a lot about their natural history. Much information was learned by the early whalers as they kept logs and detailed notes about their catch. Thus, historical accounts of the whales that were taken by whalers have yielded much information about behavior, ranges, and population levels starting in the 1800s. The killer whale was not sought after by the early whalers because it was too small and too fast so little historical information was recorded. Although killer whales are reported worldwide, there seems to be concentrations off the coasts of Antarctica, northern Japan, Iceland, Norway, Alaska, and the British Columbia/Washington areas. A unique series of events in the British Columbia/Washington area, during the last 30 years, has resulted in some of the most detailed information about killer whales in the world. |

Map (left) of the northwest coast of North America with British Columbia/Washington area within a rectangle, a main area of killer whale concentration. Map from the Friday Harbor Marina, San Juan Island, Washington. The next closest concentration of killer whales is in Alaska.

An expedition to kill an orca was sent, in 1962, by the Vancouver Aquarium to the nearby waters of the British Columbia/Washington area. The dead whale was to be used as a model for a life sized sculpture. The expedition shot a young whale but it did not die. Instead, they began to feel sorry for it and returned it to the Aquarium where it lived for a few months and captured the imagination of many visitors. During the period from 1963 to 1973 a total of 262 killer whales were captured (247 from the Puget Sound area of British Columbia/Washington) - 53 were kept, 11 died during capture and 16 died within their first year, the rest escaped or were released. These animals were shipped all over the world to oceanariums. Their presence and display changed the general public's opinion of the killer whale from a "monster to be feared" to a "cute and interesting ocean species". |

|

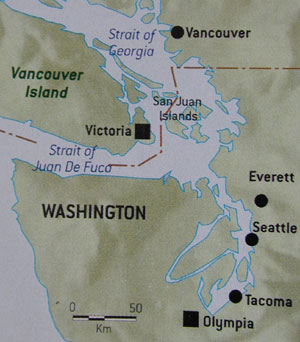

This concentrated taking of killer whales in the British Columbia/Washington area caused concern by scientists and other groups of people that it might not be good for the species. Preliminary population studies began in 1970 using questionnaires given to the fishermen, ferry drivers, and general public. In 1976 some of the first detailed studies began in the area of the San Juan Islands, Washington. This study showed that there were only 72 killer whales left here (later to be denoted the "southern community") and that 43 of the captured whales had been taken from this area. The findings of such a small population showed strong evidence that stopped the taking of killer whales for captivity in this location. This concentrated taking of killer whales in the British Columbia/Washington area caused concern by scientists and other groups of people that it might not be good for the species. Preliminary population studies began in 1970 using questionnaires given to the fishermen, ferry drivers, and general public. In 1976 some of the first detailed studies began in the area of the San Juan Islands, Washington. This study showed that there were only 72 killer whales left here (later to be denoted the "southern community") and that 43 of the captured whales had been taken from this area. The findings of such a small population showed strong evidence that stopped the taking of killer whales for captivity in this location.

Location of San Juan Islands from map at the Friday Harbor Marina, San Juan Island, Washington (right).

|

Killer whale research boat with photographer getting images of San Juan killer whales summer 2001 (above). (GA image) |

| This original study has continued in various forms since its inception and has detailed the population structure of killer whales in the San Juan Islands and surrounding area like nowhere else in the world. Much of what we know today about killer whales has come from these studies done primarily by Michael Biggs, John K. B. Ford, Graeme M. Ellis, and Kenneth Balcomb. Kenneth Balcomb's son, Kelley Balcomb-Bartok grew up doing killer whale research with his father in the San Juan Islands. He has continued his interest in the killer whale to include a passion for understanding this species, its niche in the environment, and to educate the public with unending energy to help them understand the true, scientific facts concerning the killer whales of the San Juan Islands. Kelley was the naturalist aboard the Gallant Lady (owned and operated by Patty and Roger Stewart) during the summer of 2001 for an educational tour of the San Juan Islands and their killer whale population. This trip was organized by the Resource Institute, an environmental education group based in Seattle. Our week long adventure from June 10 to 15, 2001, was made especially informative by Kelley, Patty, Roger, and Mark Anderson (the cook and representative from the Resource Institute). Every day we had new encounters and a deeper understanding of the magnificent killer whale, commonly called "orca." |

|

Two killer whales (above). (GA image) |

|

| The scientific name of the killer whale, Orcinus orca, translates into "of or belonging to realms of the dead", "a kind of whale", -or- killer whale. Before the public viewing in captivity (starting in the 1960s), killer whales had a reputation as being mean and nasty. Some of this came from the stomach contents of dead killer whales that could have numerous seals, sea lions, porpoises, and fish in their stomachs. One killer whale had 13 porpoises and 14 seals in its stomach. Also, killer whales were known to attack the "great whales," like the blue whale and the gray whale, and bite off their lips and tongues. Even though the great whales were much larger, the killer whales were more aggressive and would gang up on one whale. This type of activity made some people fear the killer whale but the oceanarium displays brought the killer whale into popularity. |

A single killer whale (above). (GA image) |

|

Three distinct groups, in the San Juan area, have been identified by researchers - residents, transients, and offshores. Within the resident population there are two communities - the northern community (found on northern Vancouver Island to southeast Alaska), and the southern community (found in southern Vancouver Island and the San Juan Islands). The southern community consists of 3 pods - (70-80 individuals). The northern community consists of about 16 pods (130-172 individuals). The transient community ranges from southeast Alaska to Washington and consists of 15-29 pods. These three groups differ in their habitat preference, feeding, general dorsal fin shape and dialects.

The offshores are generally found in pods of 30 to 60 whales. They usually stay near the edge of the continental shelf (thus the name "offshores") and rarely venture near the coast. Most of the female offshores have a dorsal fin that is recurved back, with its tip over the saddle area and an acute angle at the tip of the fin. Very little is known about this group.

The transients usually travel in pods (groups) of 2-5 whales only, feeding on marine mammals (seals, sea lions, dolphins and porpoises). Most of the females in the transient pods have a very triangular fin, with the tip centered right in the middle of the fin.

Resident whales can be found in pods of 6-50 and feed primarily on fish, especially the salmon that return to the coast every summer in the British Columbia/Washington. Most of the dorsal fins of the female residents are recurved back with the tip over the saddle but the tip is rounded instead of having the acute angle like the offshores. Genetic evidence shows that none of these three groups interbreed. In 1999 there were about 300 resident whales in British Columbia and Washington, 220 transients and 200 offshores. |

|

|

This concentrated taking of killer whales in the British Columbia/Washington area caused concern by scientists and other groups of people that it might not be good for the species. Preliminary population studies began in 1970 using questionnaires given to the fishermen, ferry drivers, and general public. In 1976 some of the first detailed studies began in the area of the San Juan Islands, Washington. This study showed that there were only 72 killer whales left here (later to be denoted the "southern community") and that 43 of the captured whales had been taken from this area. The findings of such a small population showed strong evidence that stopped the taking of killer whales for captivity in this location.

This concentrated taking of killer whales in the British Columbia/Washington area caused concern by scientists and other groups of people that it might not be good for the species. Preliminary population studies began in 1970 using questionnaires given to the fishermen, ferry drivers, and general public. In 1976 some of the first detailed studies began in the area of the San Juan Islands, Washington. This study showed that there were only 72 killer whales left here (later to be denoted the "southern community") and that 43 of the captured whales had been taken from this area. The findings of such a small population showed strong evidence that stopped the taking of killer whales for captivity in this location.